Indian Boarding Schools

In 1963, Lena Wandering Spirit became one of the more than 150,000 Indigenous children who were removed from their families and sent to residential school. Jay Cardinal Villeneuve’s short documentary Holy Angels powerfully recaptures Canada’s colonialist history through impressionistic images and the fragmented language of a child. Filmed with a fierce determination to not only uncover history but move past it, Holy Angels speaks of the resilience of a people who have found ways of healing—and of coming home again. See:

Holy Angels

by Jay Cardinal Villeneuve

—————————–

In a pounding critique of Canada’s colonial history, this short film draws parallels between the annihilation of the bison in the 1890s and the devastation inflicted on the Indigenous population by the residential school system. See:

Sisters & Brothers

by Kent Monkman

—————————–

For other titles on the subject visit:

Indigenous Peoples in Canada (First Nations and Métis) Residential Schools

We strongly suggest you consider organizing a community screening. (Hosting a community screening outside of Canada involves simply contacting their Customer Service team at info@nfb.ca)

The Society of Friends (Quakers) also had a significant role in the establishment of not only the Carlisle Indian Industrial School but others as well. In fact Friends had a significant role in establishing the policies of the BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs).

An act of Congress created a Board of Indian Commissioners April 10, 1869 and General Grant, the President elect, wrote Friends to “request that you will send him a list of names, members of your Society, whom your Society will endorse as suitable persons for Indian agents.”

For more information on this see: Handout Quaker Indian Boarding School and Handout; Quaker-BIA

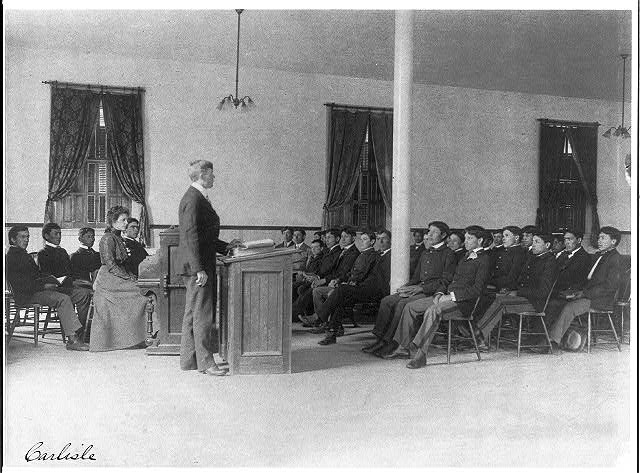

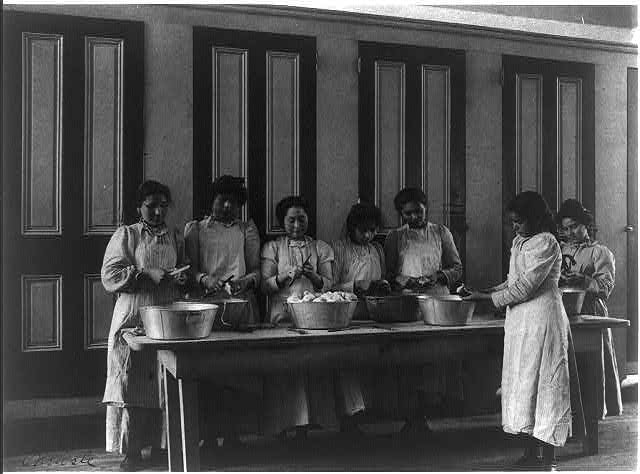

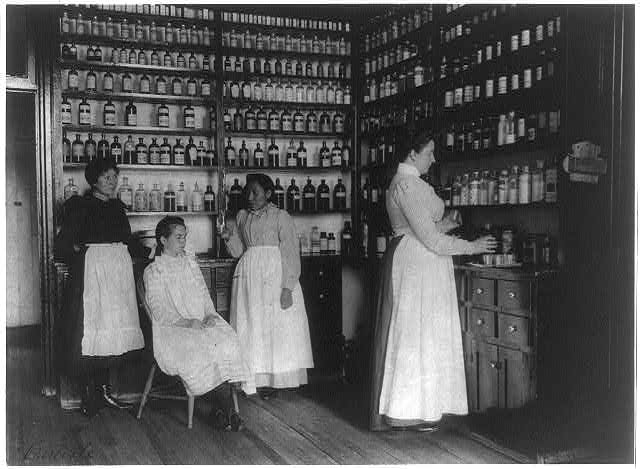

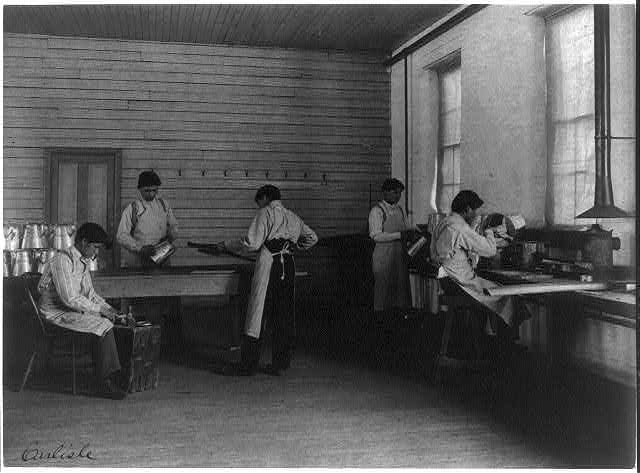

Carlisle Indian Industrial School

Carlisle Indian Industrial School is infamous as the flagship Indian boarding school. Colonel Richard H. Pratt founded the school in 1879 in an effort to help Native Americans fit into the modern industrial society that was replacing rural life in America. The intention was, as Pratt said, “to kill the Indian, but save the man.”

Funding for the school was secured from the benefactors including Quakers who often visited the school. They were treated to special programs – concerts and dramas, written and performed by the students. Many students worked in the homes and farms of Quaker families in eastern Pennsylvania and surrounding states.

In 1892, Pratt delivered a speech in which he described his philosophy behind US government-run boarding schools for American Indians. “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one,” he said. “In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Click to view larger images.

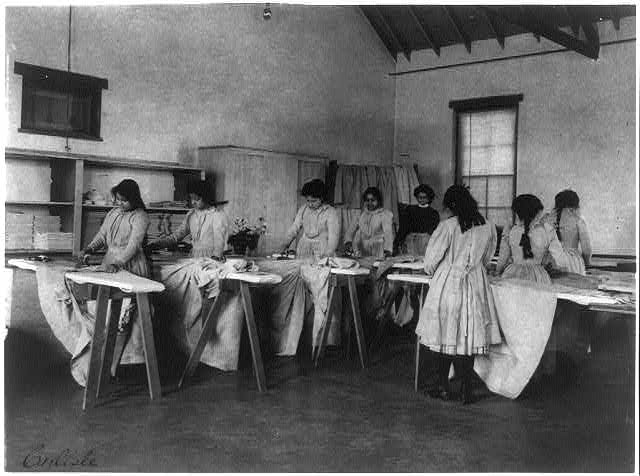

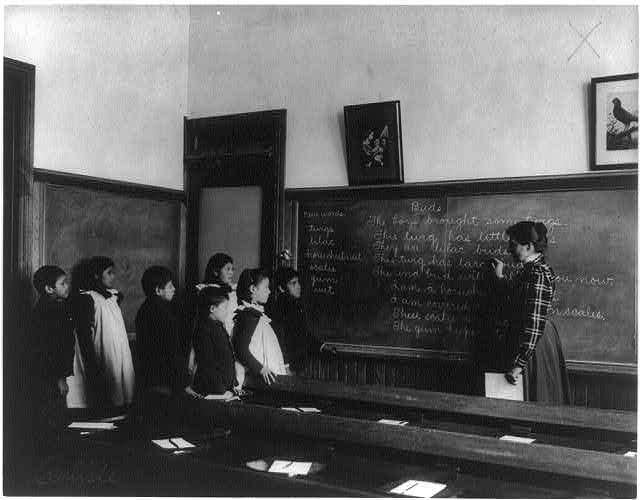

The facts are that Native children were forcibly abducted from their homes and put into Christian and government run boarding schools beginning in the mid 1800s and continuing into the 1970s. This was done pursuant to a federal policy designed to “civilize” Indians and to stamp out Native cultures; a deliberate policy of ethnocide and cultural genocide. Cut off from their families and culture, the children were punished for speaking their Native languages, banned from conducting traditional or cultural practices, shorn of traditional clothing and identity of their Native cultures, taught that their cultures and traditions were evil and sinful, and that they should be ashamed of being Native American.

In 1950 President Truman appointed Dillon S. Meyer (who ran the Japanese internment camps), as Indian Commissioner. It was the formal policy and procedure of the United States at the time to forcibly transfer indigenous children to white homes and boarding schools as a component of a strategy to “terminate” tribes as distinct peoples, meeting the essential threshold of intent under the Genocide Convention.

Other schools included The Thomas Boarding School on the Seneca Cattaraugus Nation Territory, also run by the Quakers to educate and civilize children of the Iroquois Six Nations Territories (including the Onondaga Nation). There are numerous stories of children being taken from their homes, sometimes by force, to travel long distances to live at these schools, sometimes for many years. The children were forced to cut their hair, wear military uniforms and, most tragically, stop speaking their native languages and performing their traditional ceremonies. In some cases, children were incarcerated for trying to escape, and died or were murdered in these schools. All of the students were radically transformed by these experiences. Boarding schools have had a devastating impact for generations of indigenous communities throughout North America. It would be difficult to name anything more destructive to the integrity of traditional knowledge than the boarding school program. Nearly every Native American family has been impacted by these schools.

The Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 enabled the US to ratify the Genocide Convention by manifesting its intention to stop the wholesale removal of Native children from their families and tribes. ICWA established minimal protections of due-process rights for indigenous parents and recognized the exclusive jurisdiction of existing tribal courts to adjudicate child welfare cases within reservation boundaries, also allowing tribes to intervene in state cases.

Ratified by the US in 1986, the Genocide Convention was not implemented until 1989, and then only after denying universal jurisdiction and limiting prosecutions under the act to a five-year statute of limitations for violations of the federal crime of genocide.

STORIES

In this PDF are stories of Indigenous people who experienced the horror of the Indian Residential schools in the US or Canada.

When is an honor not an honor?

by aTim Giago (Nanwica Kciji – Stands Up For Them) The full article is here… Excerpt from the article… South Dakota legislators appear to be in conflict with themselves. They are introducing a Concurrent Resolution to acknowledge and honor the Native American children...

Witness to murder at Indian Residential School

This video is of an Indigenous woman, Irene Favel describing in a CBC interview (July 8, 2008) how she witnessed the murder of a baby by staff at the Muskowekwan Indian Residential School, run by the Roman Catholic Church in Lestock, Saskatchewan.

Hundreds Died at Northern Ontario Residential Schools

by David Helwig |Dec 16, 2015 The full article is here… Excerpt from the article… Of 426 Ontario Indian residential school students known to have died from 1867 to 2000, 38 percent have been forgotten by history. New data contained in the just-released final report of...

Discovering and Researching BIA School Records

by Cody White | October 23, 2019 The full article is here… Excerpt from the article… This presentation will discuss the records of Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) boarding and day schools, looking at both individual student case files as well as general administrative...

Coalition confronts Christian boarding school trauma

by Cindy Yurth | April 3, 2014 The full article is here… Excerpt from the article… By the late 1860s, the U.S. government had expected to have the Indian problem well in hand. It had riddled the tribes with bullets, confined them to reservations, burned their crops...

0 Comments